Epidemiology

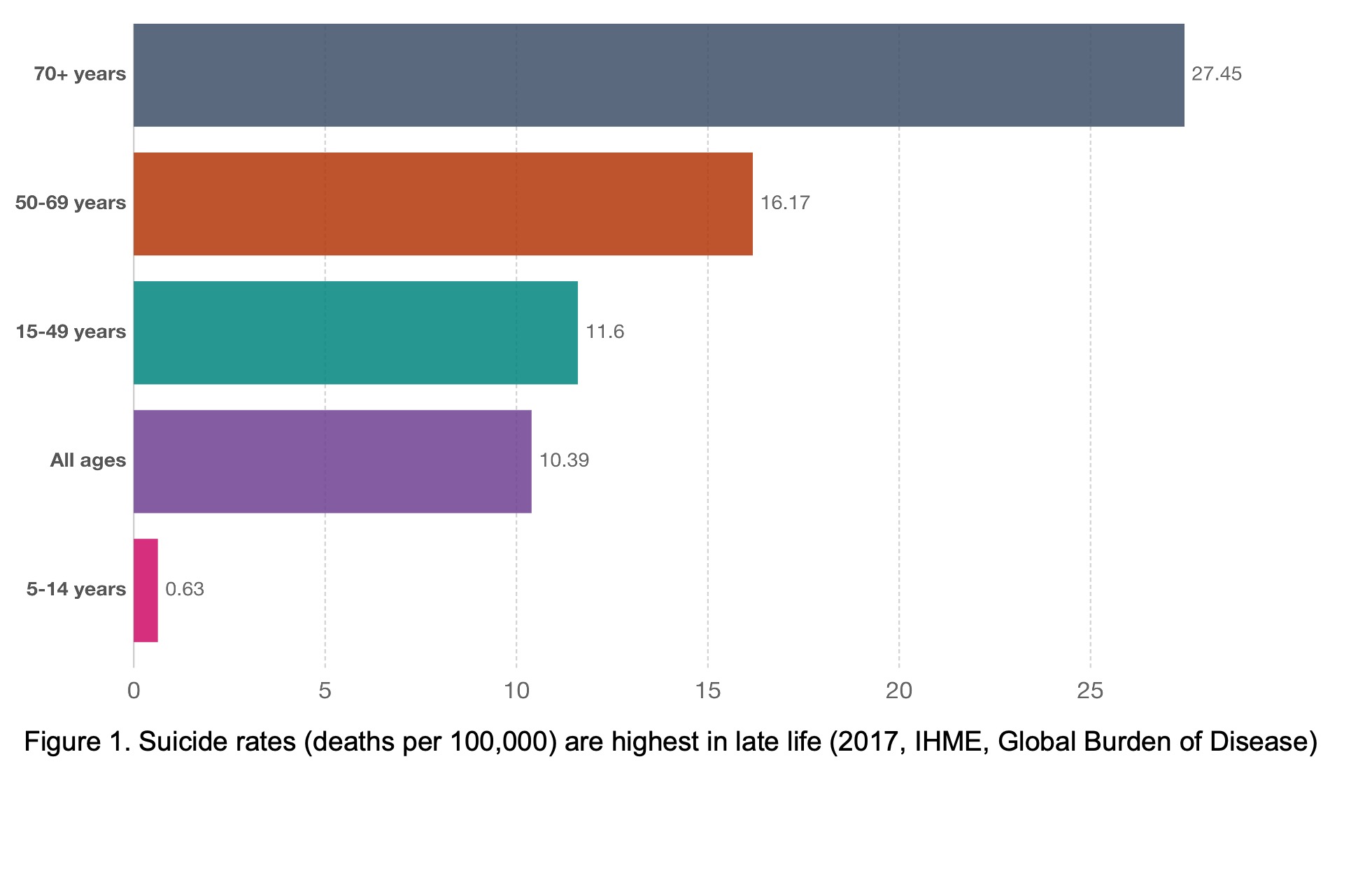

Older people are the demographic group with highest rates of suicide deaths globally (Figure 1, Global Burden of Disease Collaborative Network, 2018). Data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention indicate that suicide rates are highest among older men in the U.S.; for example, men age 80-84 had a suicide rate of 38.9 per 100,000 in 2019, compared to the overall U.S. population rate of 14.5 per 100,000. Projections indicate that suicide rates in older adults are likely to increase as current cohorts mature into older age (Phillips, 2014).

Characteristics of Older Adults Who Die by Suicide

Suicide attempts are more often fatal among older adults because this group is more likely to use more immediately lethal means (e.g., firearms), are more planful and determined, more frail, and often more isolated and thus less likely to be discovered. While most older adults die on their first attempt, a previous suicide attempt remains a potent risk factor for suicide death among older adults. A constellation of biopsychosocial factors converges among older adults at risk for suicide, which can be recalled as the 5 D’s of suicide risk in later life (Conwell, 2014; Van Orden, Silva, & Conwell, 2019). Below is information about each of these 5 D’s: depression, disability, (physical) disease, (social) disconnection, and (access to) deadly means.

- Depression:

- Mood disorders (especially Major Depression) are the most common mental disorders among older adults who die by suicide, present in 54% to 87% of older people who die by suicide.

- Few older adults who die by suicide will have received formal psychiatric diagnoses or treatment.

- The combination of depressive disorders and medical illness is particularly common in older adults who die by suicide.

- Older adults are less likely to report sad/depressed mood and endorse instead anhedonia & apathy and are more likely to describe somatic symptoms as their primary concern, including sleep, fatigue, psychomotor slowing, and problems with memory, concentration, processing speed, and executive functioning.

- Disability (i.e., functional impairment):

- Physical disability (also called functional impairment) is linked to suicide ideation, attempts, and deaths in later life.

- Greater numbers of both instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs) and activities of daily living (ADL) are associated with suicide risk.

- Sensory impairment, including vision loss, is also associated with suicide in later life.

- Most with disability do not die by suicide, but increased risk may occur in the following situations: needing assistance with ADLs (indicated by use of visiting nurse services & home health aides); residence in a long-term care facility; certain personality characteristics such as high need for control/autonomy; inflexibility in use of coping strategies; high levels of internalized ageism (associated with reduced will to live).

- There is a complex association between suicide and cognitive functioning: dementia may increase risk for suicide soon after the diagnosis and early in the illness (Seyfried, Kales, Ignacio, Conwell, & Valenstein, 2011) and cognitive control deficits increase risk for suicide attempts in later life (Szanto, 2017).

- Disease (physical illness, particularly multiple comorbidities):

- Older adults who die by suicide are characterized by: declines in physical health in the year before death, multimorbidity, and poor sleep quality.

- Older adults who die by suicide are commonly seen by their primary care physicians in the months and weeks before their deaths.

- The combination of depressive disorders and medical illness is particularly common in later life and associated with suicide.

- There is inconsistency in the literature as to which specific diseases (or organ systems) are most strongly associated with suicide and some illnesses may be associated with ideation, but not attempts or deaths.

- Potential mechanisms include: neurobiology of stress, neurobiology of illness, functional impairment (disability).

- Social disconnection (including social isolation, loneliness, family conflict, and feeling like a burden on others) is associated with suicide ideation, attempts, and deaths in later life.

- Social connections that create a sense of caring, contributing, and community have a range of benefits for health and well-being (Blazer, 2020; Holt-Lunstad, Robles, & Sbarra, 2017).

- Indicators of social disconnection are linked to suicide risk factors in later life as well as suicide ideation, attempt, and death, including: living alone, small social networks, the absence of a confidant, loss of a spouse, social (dis)engagement (e.g., not participating in social clubs/activities), family discord, and loneliness.

- Three intervention studies have shown effects on suicide deaths in older adults and all involved promoting social connection—but, the studies were not designed to directly test this mechanism (Chan et al., 2011; De Leo, Dello, & Dwyer, 2002; Oyama, Fujita, Goto, Shibuya, & Sakashita, 2006).

- Deadly means (e.g., access to firearms).

- Suicide attempts are more often fatal among older adults, in part because older adults tend to use more lethal means (e.g., firearms in the United States)

- Older adults in the United States who use firearms as the suicide method are more likely to live in rural areas and to have served in the military (Kaplan, Huguet, McFarland, & Mandle, 2012).

- Cognitive control deficits combined with access to lethal means may be a pernicious combination in later life.

- Safety Planning with older adults can be useful to address lethal means.

However, suicide in late-life is not an expected or “normal” response to aging. Rather, psychological research has demonstrated that later life is often characterized by greater well-being, more positive emotions, and better capacity to manage emotions (Charles & Carstensen, 2010). Geropsychologists have much to bring to bear on the problem of late-life suicide, including beginning to shed light on the dual truths of how later life is both a time characterized by the maintenance, and in some cases, strengthening of well-being, and at the same time, is a period of heightened risk for suicide.

Risk Assessment & Screening

Before we discuss suicide risk assessment and screening, it is helpful to remind ourselves of the purpose of doing so: the goal of a suicide risk assessment is not a prediction about whether or not an older person will die by suicide. The goal is to determine the most appropriate actions to take to keep the older person safe (Pisani, Murrie, & Silverman, 2016). It is also important to remember to take action for any and all endorsements of suicide ideation, but not the same action for every level of risk. Finally, it is also important to remember that older adults are less likely to spontaneously report suicide ideation: it is up to us to ask. Suicide risk assessments are safe and do not cause or create suicide ideation.

Suicidal thoughts are a symptom of depression, but can occur in older (and younger) adults without depression. These thoughts should always be taken seriously, as both a sign of risk and sign of distress, even if they are not an indication that someone is at imminent risk of suicide. Suicide ideation is categorized as “passive” (e.g., thoughts that one would be better off dead or wishing for death) and “active” (i.e., thoughts of killing oneself). A review of assessment tools and strategies for suicide risk in older adults in primary care is available (Raue, Ghesquiere, & Bruce, 2014). One tool for assessing both passive and active ideation is a depression screening tool, the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9).The PHQ-9 assesses the nine symptoms of depression in the DSM diagnosis of a Major Depressive Episode; the final item asks how often the respondent has had “thoughts that you would be better off dead or of hurting yourself in some way.” If an older adult reports having passive or active suicide ideation (i.e., the PHQ-9 item lumps them together), you must follow-up to determine if the ideation is “passive” or “active” and whether the respondent has current intent to act on his/her thoughts. You can follow up by asking, “in the past two weeks have you had thoughts of killing yourself?” In addition, there are routinized screeners for following up the PHQ-9, including the “P4 Screener for Assessing Suicide Risk” (Dube, Kurt, Bair, Theobald, & Williams, 2010). If a respondent reports active suicide ideation, the P4 can be administered. The 4 “p’s” in the P4 are: past suicide attempt, suicide plan, probability (perceived risk), and (lack of) preventive factors. To address risk, good clinical judgment must be exercised and any agency/clinic procedures followed as well. Actions that could be considered to address risk include: 1) expressing concern about suicide ideation and that it is not normative (to be expected) in later life, 2) obtaining consent to contact the primary care physician, 3) means safety discussions, 3) create a safety plan that addresses risk factors; 4) consult a colleague or supervisor; 5) involve the family; 6) consider increasing treatment intensity; 7) consider emergency services (ED, mobile crisis, 9-1-1).

Other relevant assessment measures include the Geriatric Suicide Ideation Scale (GSIS), which can be used to monitor changes in suicide risk across the course of treatment (Heisel & Flett, 2020). The Columbia Suicide Severity Rating Scale is considered a “gold standard” for standardized clinical interviews for suicide risk assessment.

Intervention

Several behavioral interventions have been shown (in quasi-experimental studies) to be associated with reductions in suicide rates among older adults, and all were multi-component, multi-level interventions that involved screening, connection to services, and support. Collaborative care models (CCM) that include brief psychotherapy are associated with reductions in suicidal ideation for some depressed older adults. Treating depression to remission, as well as addressing other risk factors such as functional impairment, pain, and social disconnection, are key components of suicide prevention in later life. In addition, removing access to lethal means, particularly firearms, is also a key aspect of late-life suicide prevention. Coordination of care with primary care physicians is another key aspect of late-life suicide prevention, given that many older adults who die by suicide are seen by their PCPs in the months and weeks leading up to their deaths. Finally, older adults may be less likely to disclose depression and suicide ideation, perhaps in part due to cohort differences as well as personality traits present in some older adults, including low openness to experience; thus, directly and routinely inquiring about suicide risk is key aspect of late-life suicide prevention, especially for older adults who present with depression: just as a physician regularly checks blood pressure, psychologists working with older adults must regularly assess suicide risk. Coordinating safety plans with family members or other key people in the older person’s life is also recommended, especially given that cognitive impairment may accompany suicide risk in later life.

Behavioral interventions and psychotherapies that are evidence-based for treating depression in later life can be useful for older adults at risk for suicide in the context of depressive disorders, including Problem Solving Therapy, Behavioral Activation, and Interpersonal Psychotherapy [see GeroCentral Psychotherapy page]. Addressing social connection can be useful for older adults at risk for suicide in the context of social isolation and/or loneliness, including creating a Connection Plan (Van Orden et al., 2020) including strategies to promote social connection in safety plans (Conti et al., 2020); and connecting older adults to community services, including through Area Agencies on Aging, AARP’s resources on social isolation, and the National Resource Center for Engaging Older Adults. If disability, sensory impairment, physical illness, or pain are contributing to suicide risk in older adults, coordinating with PCPs can be especially useful, as well as using psychotherapies such as Problem Solving Therapy to empower patients in self-management and coping.

Resources for Late-Life Suicide Prevention

Webinars available for viewing/downloading on Late Life Suicide Prevention:

- National Council on Aging: http://www.ncoa.org/calendar-of-events/webinars/suicide-prevention-webinar.html

- Suicide Prevention Resource Center: http://www.sprc.org/training-institute/r2p-webinars/all-listings/243

Toolkits:

- For geropsychologists working with older adults in senior living communities, there is a free toolkit available online through the SAMHSA website: http://store.samhsa.gov/product/Promoting-Emotional-Health-and-Preventing-Suicide/SMA10-4515

- For geropsychologists working with older adults in senior centers, there is a free toolkit available online through the SAMHSA website: https://store.samhsa.gov/product/Promoting-Emotional-Health-and-Preventing-Suicide/SMA15-4416

Recommended Overview Articles

Conwell, Y., Van Orden, K., & Caine, E.D. (2011). Suicide in older adults. The Psychiatric clinics of North America, 34(2), 451-68.

Conwell, Y., Van Orden, K., & Caine, E.D. (2011). Suicide in older adults. The Psychiatric clinics of North America, 34(2), 451-68.

Fassberg, M. M., et al. (2016). “A systematic review of physical illness, functional disability, and suicidal behaviour among older adults.” Aging Ment Health 20(2): 166-194. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4720055/

Fassberg, M. M., et al. (2016). “A systematic review of physical illness, functional disability, and suicidal behaviour among older adults.” Aging Ment Health 20(2): 166-194. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4720055/

Fassberg, M. M., van Orden, K. A., Duberstein, P., Erlangsen, A., Lapierre, S., Bodner, E., . . .Waern, M. (2012). A systematic review of social factors and suicidal behavior in older adulthood. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 9(3), 722-745. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3367273/

Fassberg, M. M., van Orden, K. A., Duberstein, P., Erlangsen, A., Lapierre, S., Bodner, E., . . .Waern, M. (2012). A systematic review of social factors and suicidal behavior in older adulthood. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 9(3), 722-745. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3367273/

Lutz, J., et al. (2021). “Social Disconnection in Late Life Suicide: An NIMH Workshop on State of the Research in Identifying Mechanisms, Treatment Targets, and Interventions.” Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. Conference recording.

Lutz, J., et al. (2021). “Social Disconnection in Late Life Suicide: An NIMH Workshop on State of the Research in Identifying Mechanisms, Treatment Targets, and Interventions.” Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. Conference recording.

Mezuk, B., et al. (2014). “Suicide risk in long-term care facilities: a systematic review.” Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4232590/

Mezuk, B., et al. (2014). “Suicide risk in long-term care facilities: a systematic review.” Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4232590/

Van Orden, K., & Conwell, Y. (2011). Suicides in late life. Current psychiatry reports, 13(3), 234-41.

Van Orden, K., & Conwell, Y. (2011). Suicides in late life. Current psychiatry reports, 13(3), 234-41.

Written by Kimberly Van Orden, PhD, University of Rochester Medical Center

General

Bernick, L., & Reid, J. (2005). Suicide Prevention Among Older Adults. Symposium presented at the SPRC Regions III and V Conference, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Powerpoint slides available here.

Bernick, L., & Reid, J. (2005). Suicide Prevention Among Older Adults. Symposium presented at the SPRC Regions III and V Conference, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Powerpoint slides available here.

Blazer, D. (2020). Social Isolation and Loneliness in Older Adults-A Mental Health/Public Health Challenge. JAMA Psychiatry. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2020.1054

Blazer, D. (2020). Social Isolation and Loneliness in Older Adults-A Mental Health/Public Health Challenge. JAMA Psychiatry. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2020.1054

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2013). Web-based injury statistics query and reporting system (WISQARS). Leading causes of death reports. Atlanta, GA: National Center for Injury Prevention and Control. http://www.cdc.gov/injury/wisqars/index.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2013). Web-based injury statistics query and reporting system (WISQARS). Leading causes of death reports. Atlanta, GA: National Center for Injury Prevention and Control. http://www.cdc.gov/injury/wisqars/index.html

Charles, S.T., & Carstensen, L.L. (2010). Social and emotional aging. Annual Review of Psychology, 61, 383-409

Charles, S.T., & Carstensen, L.L. (2010). Social and emotional aging. Annual Review of Psychology, 61, 383-409

Conwell, Y. (2014). Suicide later in life: challenges and priorities for prevention. Am J Prev Med, 47(3 Suppl 2), S244-250. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2014.05.040

Conwell, Y. (2014). Suicide later in life: challenges and priorities for prevention. Am J Prev Med, 47(3 Suppl 2), S244-250. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2014.05.040

Conwell, Y., Dubertstein, P.R., & Caine, E.D. (2002). Risk factors for suicide in later life. Biological Psychiatry, 52(3), 193-204.

Conwell, Y., Dubertstein, P.R., & Caine, E.D. (2002). Risk factors for suicide in later life. Biological Psychiatry, 52(3), 193-204.

Conwell, Y., Rotenberg, M., & Caine, E.D. (1990). Completed suicide at age 50 and over. Journal of the American Geriatric Society, 38(6), 640-4.

Conwell, Y., Rotenberg, M., & Caine, E.D. (1990). Completed suicide at age 50 and over. Journal of the American Geriatric Society, 38(6), 640-4.

Conwell, Y., Van Orden, K., & Caine, E.D. (2011). Suicide in older adults. The Psychiatric clinics of North America, 34(2), 451-68.

Conwell, Y., Van Orden, K., & Caine, E.D. (2011). Suicide in older adults. The Psychiatric clinics of North America, 34(2), 451-68.

Duberstein, P.R. (1995) Openness to experience and completed suicide across the second half of life. International Psychogeriatrics, 7(2), 183-198.

Duberstein, P.R. (1995) Openness to experience and completed suicide across the second half of life. International Psychogeriatrics, 7(2), 183-198.

Fassberg, M. M., et al. (2016). “A systematic review of physical illness, functional disability, and suicidal behaviour among older adults.” Aging Ment Health 20(2): 166-194. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4720055/

Fassberg, M. M., et al. (2016). “A systematic review of physical illness, functional disability, and suicidal behaviour among older adults.” Aging Ment Health 20(2): 166-194. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4720055/

Fassberg, M. M., van Orden, K. A., Duberstein, P., Erlangsen, A., Lapierre, S., Bodner, E., . . .Waern, M. (2012). A systematic review of social factors and suicidal behavior in older adulthood. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 9(3), 722-745. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3367273/

Fassberg, M. M., van Orden, K. A., Duberstein, P., Erlangsen, A., Lapierre, S., Bodner, E., . . .Waern, M. (2012). A systematic review of social factors and suicidal behavior in older adulthood. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 9(3), 722-745. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3367273/

Heron, M.P., Hoyert, D.L., Murphy, S.L., Jiaquan, X., Kochanek, K.D., & Tejada-Vera, B. (2009) Deaths: Final Data for 2006. National Vital Statistics Reports, 57(14), 1-135.

Heron, M.P., Hoyert, D.L., Murphy, S.L., Jiaquan, X., Kochanek, K.D., & Tejada-Vera, B. (2009) Deaths: Final Data for 2006. National Vital Statistics Reports, 57(14), 1-135.

Holt-Lunstad, J., Robles, T. F., & Sbarra, D. A. (2017). Advancing social connection as a public health priority in the United States. Am Psychol, 72(6), 517-530. doi:10.1037/amp0000103

Holt-Lunstad, J., Robles, T. F., & Sbarra, D. A. (2017). Advancing social connection as a public health priority in the United States. Am Psychol, 72(6), 517-530. doi:10.1037/amp0000103

Kaplan, M. S., Huguet, N., McFarland, B. H., & Mandle, J. A. (2012). Factors associated with suicide by firearm among U.S. older adult men. Psychol. Men Masc., 13(1), 65-74.

Kaplan, M. S., Huguet, N., McFarland, B. H., & Mandle, J. A. (2012). Factors associated with suicide by firearm among U.S. older adult men. Psychol. Men Masc., 13(1), 65-74.

Luoma, J. B., Martin, C. E., & Pearson, J. L. (2002). Contact with mental health and primary care providers before suicide: A review of the evidence. American Journal of Psychiatry, 159(6), 909-916.

Luoma, J. B., Martin, C. E., & Pearson, J. L. (2002). Contact with mental health and primary care providers before suicide: A review of the evidence. American Journal of Psychiatry, 159(6), 909-916.

Lutz, J., et al. (2021). “Social Disconnection in Late Life Suicide: An NIMH Workshop on State of the Research in Identifying Mechanisms, Treatment Targets, and Interventions.” Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. Conference recording.

Lutz, J., et al. (2021). “Social Disconnection in Late Life Suicide: An NIMH Workshop on State of the Research in Identifying Mechanisms, Treatment Targets, and Interventions.” Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. Conference recording.

McIntosh, J.L., & Santos JF. (1985). Methods of suicide by age: Sex and race differences among the young and old. International Journal of Aging & Human Development, 22(2), 123-39.

McIntosh, J.L., & Santos JF. (1985). Methods of suicide by age: Sex and race differences among the young and old. International Journal of Aging & Human Development, 22(2), 123-39.

Mezuk, B., et al. (2014). “Suicide risk in long-term care facilities: a systematic review.” Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4232590/

Mezuk, B., et al. (2014). “Suicide risk in long-term care facilities: a systematic review.” Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4232590/

Murphy, E., Kapur, N., Webb, R., Purandare, N., Hawton, K., Bergen, H., . . . Cooper, J. (2012). Risk factors for repetition and suicide following self-harm in older adults: Multicentre cohort study. British Journal of Psychiatry, 200, 399-404.

Murphy, E., Kapur, N., Webb, R., Purandare, N., Hawton, K., Bergen, H., . . . Cooper, J. (2012). Risk factors for repetition and suicide following self-harm in older adults: Multicentre cohort study. British Journal of Psychiatry, 200, 399-404.

Phillips, J. A. (2014). A changing epidemiology of suicide? The influence of birth cohorts on suicide rates in the United States. Soc Sci Med, 114C, 151-160. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.05.038

Phillips, J. A. (2014). A changing epidemiology of suicide? The influence of birth cohorts on suicide rates in the United States. Soc Sci Med, 114C, 151-160. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.05.038

Szanto, K. (2017). Cognitive Deficits: Underappreciated Contributors to Suicide. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. doi:10.1016/j.jagp.2017.02.012

Szanto, K. (2017). Cognitive Deficits: Underappreciated Contributors to Suicide. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. doi:10.1016/j.jagp.2017.02.012

Van Orden, K. A., Silva, C., & Conwell, Y. (2019). Suicide in Later Life. In B. Knight (Ed.), Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Psychology (Psychology and Aging). Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Van Orden, K. A., Silva, C., & Conwell, Y. (2019). Suicide in Later Life. In B. Knight (Ed.), Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Psychology (Psychology and Aging). Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Van Orden, K., & Conwell, Y. (2011). Suicides in late life. Current psychiatry reports, 13(3), 234-41.

Van Orden, K., & Conwell, Y. (2011). Suicides in late life. Current psychiatry reports, 13(3), 234-41.

World Health Organization. (2002). Distribution of suicides rates (per 100,000), by gender and age, 2000, 2002. Retrieved from: http://www.who.int/mental_health/prevention/suicide/suicide_rates_chart/en/index.html

World Health Organization. (2002). Distribution of suicides rates (per 100,000), by gender and age, 2000, 2002. Retrieved from: http://www.who.int/mental_health/prevention/suicide/suicide_rates_chart/en/index.html

Assessment

Look at the extensive assessment database of geriatric measures from the University of Alabama’s Alabama Research Institute on Aging! Register for access to the database HERE.

Dube, P., Kurt, K., Bair, M. J., Theobald, D., & Williams, L. S. (2010). The P4 screener: Evaluation of a brief measure of assessing potential suicide risk in randomized effectiveness trials of primary care and oncology patients. Primary care companion to the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 12, doi: 10.4088/PCC.10m00978blu

Dube, P., Kurt, K., Bair, M. J., Theobald, D., & Williams, L. S. (2010). The P4 screener: Evaluation of a brief measure of assessing potential suicide risk in randomized effectiveness trials of primary care and oncology patients. Primary care companion to the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 12, doi: 10.4088/PCC.10m00978blu

Fremouw, W., McCoy, K., Tyner, E., & Musick, R. (2009). Suicide Older Adult Protocol – SOAP. Unpublished manuscript, West Virginia University. ACCESS MANUAL HERE.

Fremouw, W., McCoy, K., Tyner, E., & Musick, R. (2009). Suicide Older Adult Protocol – SOAP. Unpublished manuscript, West Virginia University. ACCESS MANUAL HERE.

Global Burden of Disease Collaborative Network. (2018). Global Burden of Disease Study 2017 (GBD 2017) Results. Retrieved from Seattle, United States: http://ghdx.healthdata.org/gbd-results-tool

Global Burden of Disease Collaborative Network. (2018). Global Burden of Disease Study 2017 (GBD 2017) Results. Retrieved from Seattle, United States: http://ghdx.healthdata.org/gbd-results-tool

Heisel, M. J., & Flett, G. L. (2006). The development and initial validation of the Geriatric Suicide Ideation Scale. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 14, 742-751.

Heisel, M. J., & Flett, G. L. (2006). The development and initial validation of the Geriatric Suicide Ideation Scale. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 14, 742-751.

Heisel, M. J., & Flett, G. L. (2020). Screening for suicide risk among older adults: assessing preliminary psychometric properties of the Brief Geriatric Suicide Ideation Scale (BGSIS) and the GSIS-Screen. Aging Ment Health, 1-15. doi:10.1080/13607863.2020.1857690

Heisel, M. J., & Flett, G. L. (2020). Screening for suicide risk among older adults: assessing preliminary psychometric properties of the Brief Geriatric Suicide Ideation Scale (BGSIS) and the GSIS-Screen. Aging Ment Health, 1-15. doi:10.1080/13607863.2020.1857690

Oyama. H., Fujita, M., Goto, M., Shibuya, H., & Sakashita, T. (2006). Outcomes of community-based screening for depression and suicide prevention among Japanese elders. Gerontologist, 46(6), 821-26.

Oyama. H., Fujita, M., Goto, M., Shibuya, H., & Sakashita, T. (2006). Outcomes of community-based screening for depression and suicide prevention among Japanese elders. Gerontologist, 46(6), 821-26.

Pisani, A. R., Murrie, D. C., & Silverman, M. M. (2016). Reformulating Suicide Risk Formulation: From Prediction to Prevention. Acad Psychiatry, 40(4), 623-629. doi:10.1007/s40596-015-0434-6

Pisani, A. R., Murrie, D. C., & Silverman, M. M. (2016). Reformulating Suicide Risk Formulation: From Prediction to Prevention. Acad Psychiatry, 40(4), 623-629. doi:10.1007/s40596-015-0434-6

Raue, P. J., Ghesquiere, A. R., & Bruce, M. L. (2014). Suicide risk in primary care: identification and management in older adults. Curr Psychiatry Rep, 16(9), 466. doi:10.1007/s11920-014-0466-8

Raue, P. J., Ghesquiere, A. R., & Bruce, M. L. (2014). Suicide risk in primary care: identification and management in older adults. Curr Psychiatry Rep, 16(9), 466. doi:10.1007/s11920-014-0466-8

Reiss, N.S. & Tishler, C.L. (2008). Suicidality in nursing home residents: Part I. Prevalence, risk factors, methods, assessment, and management. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 39(3), 264-270. doi: 10.1037/0735-7028.39.3.264

Reiss, N.S. & Tishler, C.L. (2008). Suicidality in nursing home residents: Part I. Prevalence, risk factors, methods, assessment, and management. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 39(3), 264-270. doi: 10.1037/0735-7028.39.3.264

Seyfried, L. S., Kales, H. C., Ignacio, R. V., Conwell, Y., & Valenstein, M. (2011). Predictors of suicide in patients with dementia. Alzheimers Dement, 7(6), 567-573. doi:10.1016/j.jalz.2011.01.006

Seyfried, L. S., Kales, H. C., Ignacio, R. V., Conwell, Y., & Valenstein, M. (2011). Predictors of suicide in patients with dementia. Alzheimers Dement, 7(6), 567-573. doi:10.1016/j.jalz.2011.01.006

Szanto, K. (2017). Cognitive Deficits: Underappreciated Contributors to Suicide. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. doi:10.1016/j.jagp.2017.02.012

Szanto, K. (2017). Cognitive Deficits: Underappreciated Contributors to Suicide. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. doi:10.1016/j.jagp.2017.02.012

Treatment

Alexopoulos, G. S., Reynolds, C. F., 3rd, Bruce, M. L., Katz, I. R., Raue, P. J., Mulsant, B. H., . . . Group, P. (2009). Reducing suicidal ideation and depression in older primary care patients: 24-month outcomes of the PROSPECT study. American Journal of Psychiatry, 166(8), 882-890.

Alexopoulos, G. S., Reynolds, C. F., 3rd, Bruce, M. L., Katz, I. R., Raue, P. J., Mulsant, B. H., . . . Group, P. (2009). Reducing suicidal ideation and depression in older primary care patients: 24-month outcomes of the PROSPECT study. American Journal of Psychiatry, 166(8), 882-890.

Chan, S.S., Leung, V.P., Tsoh, J., Li, S.W., Yu, C.S., Yu, G.K., et al. (2011). Outcomes of a two-tiered multifaceted elderly suicide prevention program in a Hong Kong Chinese community. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 19(2):185-96.

Chan, S.S., Leung, V.P., Tsoh, J., Li, S.W., Yu, C.S., Yu, G.K., et al. (2011). Outcomes of a two-tiered multifaceted elderly suicide prevention program in a Hong Kong Chinese community. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 19(2):185-96.

Conti, E. C., Jahn, D. R., Simons, K. V., Edinboro, L. P. C., Jacobs, M. L., Vinson, L., . . . Van Orden, K. A. (2020). Safety Planning to Manage Suicide Risk with Older Adults: Case Examples and Recommendations. Clin Gerontol, 43(1), 104-109. doi:10.1080/07317115.2019.1611685

Conti, E. C., Jahn, D. R., Simons, K. V., Edinboro, L. P. C., Jacobs, M. L., Vinson, L., . . . Van Orden, K. A. (2020). Safety Planning to Manage Suicide Risk with Older Adults: Case Examples and Recommendations. Clin Gerontol, 43(1), 104-109. doi:10.1080/07317115.2019.1611685

De Leo, D., Carollo, G., Dello Buono, M. (1995). Lower suicide rates associated with a Tele-Help/Tele-Check service for the elderly at home. American Journal of Psychiatry, 152(4), 632-4.

De Leo, D., Carollo, G., Dello Buono, M. (1995). Lower suicide rates associated with a Tele-Help/Tele-Check service for the elderly at home. American Journal of Psychiatry, 152(4), 632-4.

De Leo, D., Dello Buono, M., & Dwyer, J. (2002). Suicide among the elderly: the long-term impact of a telephone support and assessment intervention in northern Italy. British Journal of Psychiatry, 181, 226-9.

De Leo, D., Dello Buono, M., & Dwyer, J. (2002). Suicide among the elderly: the long-term impact of a telephone support and assessment intervention in northern Italy. British Journal of Psychiatry, 181, 226-9.

Heisel, M. J., Talbot, N. L., King, D. A., Tu, X. M., & Duberstein, P. R. (2015). Adapting interpersonal psychotherapy for older adults at risk for suicide. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 23(1), 87-98.

Heisel, M. J., Talbot, N. L., King, D. A., Tu, X. M., & Duberstein, P. R. (2015). Adapting interpersonal psychotherapy for older adults at risk for suicide. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 23(1), 87-98.

Oyama, H., Sakashita, T., Ono, Y., Goto, M., Fujita, M., & Koida J. (2008). Effect of community-based intervention using depression screening on elderly suicide risk: A meta-analysis of the evidence from Japan. Community Mental Health Journal, 44(5), 311-20.

Oyama, H., Sakashita, T., Ono, Y., Goto, M., Fujita, M., & Koida J. (2008). Effect of community-based intervention using depression screening on elderly suicide risk: A meta-analysis of the evidence from Japan. Community Mental Health Journal, 44(5), 311-20.

Raue, P. J., Ghesquiere, A. R., & Bruce, M. L. (2014). Suicide risk in primary care: identification and management in older adults. Curr Psychiatry Rep, 16(9), 466. doi:10.1007/s11920-014-0466-8

Raue, P. J., Ghesquiere, A. R., & Bruce, M. L. (2014). Suicide risk in primary care: identification and management in older adults. Curr Psychiatry Rep, 16(9), 466. doi:10.1007/s11920-014-0466-8

Reiss, N.S. & Tishler, C.L. (2008). Suicidality in nursing home residents: Part I. Prevalence, risk factors, methods, assessment, and management. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 39(3), 264-270. doi: 10.1037/0735-7028.39.3.264

Reiss, N.S. & Tishler, C.L. (2008). Suicidality in nursing home residents: Part I. Prevalence, risk factors, methods, assessment, and management. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 39(3), 264-270. doi: 10.1037/0735-7028.39.3.264

Unutzer, J., Katon, W., Callahan, C. M., Williams, J. W., Jr., Hunkeler, E., Harpole, L., . . . Treatment, I. I. I. M.-P. A. t. C. (2002). Collaborative care management of late-life depression in the primary care setting: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA, 288(22), 2836-2845.

Unutzer, J., Katon, W., Callahan, C. M., Williams, J. W., Jr., Hunkeler, E., Harpole, L., . . . Treatment, I. I. I. M.-P. A. t. C. (2002). Collaborative care management of late-life depression in the primary care setting: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA, 288(22), 2836-2845.

Van Orden, K. A., Bower, E., Lutz, J., Silva, C., Gallegos, A. M., Podgorski, C. A., . . . Conwell, Y. (2020). Strategies to Promote Social Connections Among Older Adults During ‘Social Distancing’ Restrictions. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. doi:10.1016/j.jagp.2020.05.004

Van Orden, K. A., Bower, E., Lutz, J., Silva, C., Gallegos, A. M., Podgorski, C. A., . . . Conwell, Y. (2020). Strategies to Promote Social Connections Among Older Adults During ‘Social Distancing’ Restrictions. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. doi:10.1016/j.jagp.2020.05.004

Webinars available for viewing/downloading on Late Life Suicide Prevention:

National Council on Aging: http://www.ncoa.org/calendar-of-events/webinars/suicide-prevention-webinar.html

Suicide Prevention Resource Center: http://www.sprc.org/training-institute/r2p-webinars/all-listings/243

For geropsychologists working with older adults in senior living communities, there is a free toolkit available online through the SAMHSA website:

http://store.samhsa.gov/product/Promoting-Emotional-Health-and-Preventing-Suicide/SMA10-4515